Post by Admin on Oct 5, 2019 15:09:27 GMT -4

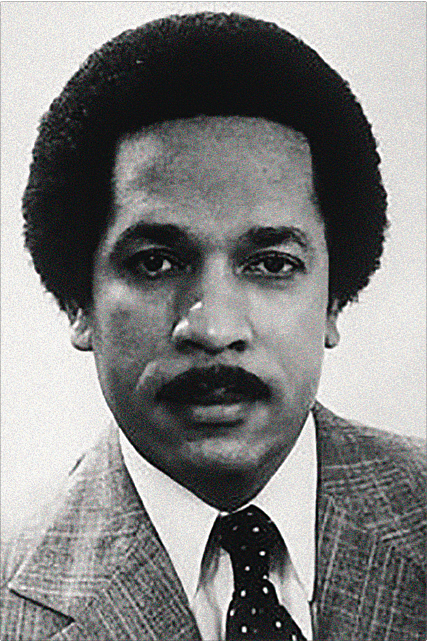

Max Robinson Was The First African American Broadcast Network News Anchor In The History

Max Robinson, in full Maxie Cleveland Robinson, Jr., (born May 1, 1939, Richmond, Va., U.S.—died Dec. 20, 1988, Washington, D.C.), American television journalist and the first African American man to anchor a nightly network newscast. Robinson was also the first African American to anchor a local news program in Washington, D.C.

Robinson’s first journalism job began and ended in 1959, when he was hired to read news at a Portsmouth, Va., television station. Although the station selected him over an otherwise all-white group of applicants, it still enforced a colour barrier by projecting an image of the station’s logo to conceal Robinson as he read the news. He was fired the day after he presented the news without the logo obscuring his face. In 1965 he joined WTOP-TV in Washington, D.C., as a correspondent and camera operator, but he moved quickly to nearby WRC-TV, where he won awards for coverage of race riots and a documentary on life in poor urban neighbourhoods. He was hired back by WTOP as its first African American news anchor in 1969 and stayed there until 1978. Robinson moved to Chicago when ABC News chose him as one of three coanchors for ABC’s World News Tonight. The anchor arrangement ended with the death of coanchor Frank Reynolds in 1983. Robinson left ABC News shortly thereafter and joined Chicago’s WMAQ-TV as a news anchor (1984–87).

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Possibly seeking refuge from the mounting pressure, Robinson, having earned an Emmy for his reportage, began to drink, which was followed by bouts of depression. By 1985, his glorious ride to the top was beginning to unravel and he was relegated to weekend anchoring and spot news from Chicago at WMAQ-TV.

This was the beginning of the end of his journalistic venture, with only a few irregular freelance jobs keeping him afloat after retiring from WMAQ-TV. Much of his time was taken up with recovering from the alcoholism that took him in and out of several treatment centers. His physical health was soon compromised again when he was hospitalized for pneumonia. From this illness and further study by a team of doctors, he was diagnosed with AIDS.

His retreat from public life was now increased with the affliction of AIDS, which brought him shame. Not until 1988 did he make a public appearance in St. Louis at the National Association of Black Journalists convention, an organization in which he was among the founding members.

Several months later, Robinson ignored family and friends’ request to stay home and rest when he was invited to speak at a reception at Howard University. He died in Washington, D.C., Dec. 20. He was 49. He told the Rev. Jesse Jackson that he had not contracted AIDS from homosexuality but from “promiscuity … let my predicament be a source of education to our people.”

“Max had a tremendous impact on our organization and its membership,” said DeWayne Wickham, at that time president of the National Association of Black Journalists. “He was more than a simple legend. Max Robinson was a hero in a profession not known for its good guys … by his success he epitomized the hopes and aspirations of thousands of Black journalists, and in his failure Max brought home to our membership the frailties of our existence in this industry.”

Robinson, according to remarks from newscaster Bernard Shaw, was “Engine No. 1. His impact will go on for generations.”

Some of his legacy is certainly found in the increased presence of Black journalists on television in major markets. His legacy endures, too, in the success of his siblings, none more noteworthy than author and activist Randall Robinson.

Jackson, Robinson’s close friend, delivered the eulogy, saying, “Max … wouldn’t adjust, wouldn’t knuckle under in the face of obvious, and not so obvious racism.”

Max Robinson, in full Maxie Cleveland Robinson, Jr., (born May 1, 1939, Richmond, Va., U.S.—died Dec. 20, 1988, Washington, D.C.), American television journalist and the first African American man to anchor a nightly network newscast. Robinson was also the first African American to anchor a local news program in Washington, D.C.

Robinson’s first journalism job began and ended in 1959, when he was hired to read news at a Portsmouth, Va., television station. Although the station selected him over an otherwise all-white group of applicants, it still enforced a colour barrier by projecting an image of the station’s logo to conceal Robinson as he read the news. He was fired the day after he presented the news without the logo obscuring his face. In 1965 he joined WTOP-TV in Washington, D.C., as a correspondent and camera operator, but he moved quickly to nearby WRC-TV, where he won awards for coverage of race riots and a documentary on life in poor urban neighbourhoods. He was hired back by WTOP as its first African American news anchor in 1969 and stayed there until 1978. Robinson moved to Chicago when ABC News chose him as one of three coanchors for ABC’s World News Tonight. The anchor arrangement ended with the death of coanchor Frank Reynolds in 1983. Robinson left ABC News shortly thereafter and joined Chicago’s WMAQ-TV as a news anchor (1984–87).

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Possibly seeking refuge from the mounting pressure, Robinson, having earned an Emmy for his reportage, began to drink, which was followed by bouts of depression. By 1985, his glorious ride to the top was beginning to unravel and he was relegated to weekend anchoring and spot news from Chicago at WMAQ-TV.

This was the beginning of the end of his journalistic venture, with only a few irregular freelance jobs keeping him afloat after retiring from WMAQ-TV. Much of his time was taken up with recovering from the alcoholism that took him in and out of several treatment centers. His physical health was soon compromised again when he was hospitalized for pneumonia. From this illness and further study by a team of doctors, he was diagnosed with AIDS.

His retreat from public life was now increased with the affliction of AIDS, which brought him shame. Not until 1988 did he make a public appearance in St. Louis at the National Association of Black Journalists convention, an organization in which he was among the founding members.

Several months later, Robinson ignored family and friends’ request to stay home and rest when he was invited to speak at a reception at Howard University. He died in Washington, D.C., Dec. 20. He was 49. He told the Rev. Jesse Jackson that he had not contracted AIDS from homosexuality but from “promiscuity … let my predicament be a source of education to our people.”

“Max had a tremendous impact on our organization and its membership,” said DeWayne Wickham, at that time president of the National Association of Black Journalists. “He was more than a simple legend. Max Robinson was a hero in a profession not known for its good guys … by his success he epitomized the hopes and aspirations of thousands of Black journalists, and in his failure Max brought home to our membership the frailties of our existence in this industry.”

Robinson, according to remarks from newscaster Bernard Shaw, was “Engine No. 1. His impact will go on for generations.”

Some of his legacy is certainly found in the increased presence of Black journalists on television in major markets. His legacy endures, too, in the success of his siblings, none more noteworthy than author and activist Randall Robinson.

Jackson, Robinson’s close friend, delivered the eulogy, saying, “Max … wouldn’t adjust, wouldn’t knuckle under in the face of obvious, and not so obvious racism.”