Post by Admin on Aug 3, 2020 13:25:08 GMT -4

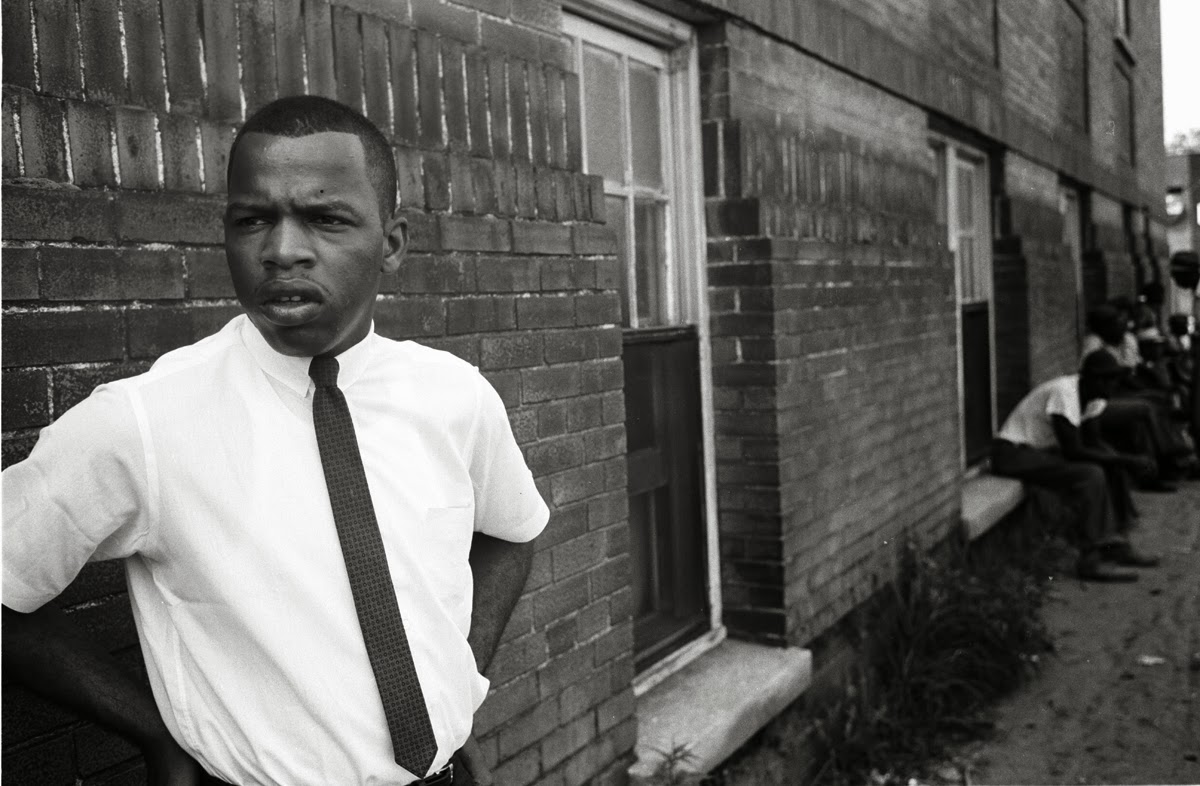

John Robert Lewis (February 21, 1940 – July 17, 2020) was an American politician and civil-rights leader who served in the United States House of Representatives for Georgia's 5th congressional district from 1987 until his death in 2020 from pancreatic cancer. Lewis served as the chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) from 1963 to 1966.

Lewis was one of the "Big Six" leaders of groups who organized the 1963 March on Washington, and he fulfilled many key roles in the civil rights movement and its actions to end legalized racial segregation in the United States. In 1965, Lewis led the first of three Selma to Montgomery marches across the Edmund Pettus Bridge. In an incident which became known as Bloody Sunday, state troopers and police then attacked the marchers, including Lewis.

A member of the Democratic Party, Lewis was first elected to Congress in 1986 and served for 17 terms in the U.S. House of Representatives. Due to his length of service, he became the dean of the Georgia congressional delegation. The district he represented includes the northern three-quarters of Atlanta.

He was a leader of the Democratic Party in the U.S. House of Representatives, serving from 1991 as a Chief Deputy Whip and from 2003 as Senior Chief Deputy Whip. Lewis received many honorary degrees and awards, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Early life and education

John Robert Lewis was born on February 21, 1940, just outside Troy, Alabama, the third of ten children of Willie Mae (née Carter) and Eddie Lewis. His parents were sharecroppers in rural Pike County, Alabama.

As a boy, Lewis aspired to be a preacher; at age five, he was preaching to his family's chickens on the farm. As a young child, Lewis had little interaction with white people; by the time he was six, Lewis had seen only two white people in his life. As he grew older he began taking trips into town with his family, where he experienced racism and segregation, such as at the public library in Troy. Lewis had relatives who lived in northern cities, and he learned from them that the North had integrated schools, buses, and businesses. When Lewis was 11, an uncle took him on a trip to Buffalo, New York, making him more acutely aware of Troy's segregation.

In 1955, Lewis first heard Martin Luther King Jr. on the radio and he closely followed King's Montgomery bus boycott later that year. At age 15, Lewis preached his first public sermon. Lewis met Rosa Parks when he was 17, and met King for the first time when he was 18.

Lewis graduated from the American Baptist Theological Seminary in Nashville, Tennessee and was ordained as a Baptist minister. He then received a bachelor's degree in religion and philosophy from Fisk University. He was a member of Phi Beta Sigma fraternity.

Lewis did not receive a driver license until he was in his 40s and was driven around by Grant Lewis, his younger brother.

As a student, he was dedicated to the civil rights movement. He organized sit-ins at segregated lunch counters in Nashville and took part in many other civil rights activities as part of the Nashville Student Movement. The Nashville sit-in movement was responsible for the desegregation of lunch counters in downtown Nashville. Lewis was arrested and jailed many times in the nonviolent movement to desegregate the downtown area of the city. He was also instrumental in organizing bus boycotts and other nonviolent protests in the fight for voter and racial equality.

It was during this time that he first expressed the need to engage in "good trouble, necessary trouble" to achieve change, and he held by the phrase and the sentiment throughout his life.

While a student, Lewis was invited to attend nonviolence workshops held at Clark Memorial United Methodist Church by the Rev. James Lawson and Rev. Kelly Miller Smith. There, Lewis and other students became dedicated adherents to the discipline and philosophy of nonviolence, which he practiced for the rest of his

life.

In 1961, Lewis became one of the 13 original Freedom Riders. They were seven whites and six blacks who were determined to ride from Washington, D.C. to New Orleans in an integrated fashion. At that time, several southern states continued to enforce laws prohibiting black and white riders from sitting next to each other on public transportation. The Freedom Ride, originated by the Fellowship of Reconciliation and revived by James Farmer and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), was initiated to pressure the federal government to enforce the Supreme Court decision in Boynton v. Virginia (1960) that declared segregated interstate bus travel to be unconstitutional. The Freedom Rides also exposed the passivity of the government regarding violence against citizens of the country who were simply acting in accordance with the law. The federal government had trusted the notoriously racist Alabama police to protect the Riders, but did nothing itself, except to have FBI agents take notes. The Kennedy Administration then called for a cooling-off period, with a moratorium on Freedom Rides.

In the South, Lewis and other nonviolent Freedom Riders were beaten by angry mobs, arrested at times and taken to jail. At age 21, Lewis was the first of the Freedom Riders to be assaulted while in Rock Hill, South Carolina. He tried to enter a whites-only waiting room and two white men attacked him, injuring his face and kicking him in the ribs. Nevertheless, only two weeks later Lewis joined a Freedom Ride that was bound for Jackson, Mississippi. "We were determined not to let any act of violence keep us from our goal. We knew our lives could be threatened, but we had made up our minds not to turn back," Lewis said towards the end of his life in regard to his perseverance following the act of violence. Lewis was also imprisoned for 40 days in the Mississippi State Penitentiary in Sunflower County, after participating in a Freedom Riders activity in that state.

In an interview with CNN during the 40th anniversary of the Freedom Rides, Lewis recounted the amount of violence he and the 12 other original Freedom Riders endured. In Birmingham, the Riders were beaten with baseball bats, chains, lead pipes, and stones. They were arrested by police who led them across the border into Tennessee and let them go. They reorganized and rode to Montgomery where they were met with more violence, and Lewis was hit in the head with a wooden crate. "It was very violent. I thought I was going to die. I was left lying at the Greyhound bus station in Montgomery unconscious," said Lewis, remembering the incident. When CORE gave up on the Freedom Ride because of the violence, Lewis and fellow activist Diane Nash arranged for the Nashville students to take it over and bring it to a successful conclusion.

In February 2009, 48 years after he was bloodied in a Greyhound station during a Freedom Ride, Lewis received a nationally televised apology from a white southerner and former Klansman, Elwin Wilson.

Lewis wrote in 2015 that he personally knew Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman, who, along with James Chaney, were abducted and murdered in June 1964 in Neshoba County, Mississippi, by members of the Ku Klux Klan.

Lewis supported Hillary Clinton in the 2016 Democratic presidential primaries against Bernie Sanders. Regarding Sanders's role in the civil rights movement, Lewis remarked "To be very frank, I never saw him, I never met him. I chaired the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee for three years, from 1963 to 1966. I was involved in sit-ins, in the Freedom Rides, the March on Washington, the March from Selma to Montgomery... but I met Hillary Clinton". Former Congressman and Hawaii Governor Neil Abercrombie wrote a letter to Lewis expressing his disappointment with Lewis's comments on Sanders. Lewis later clarified his statement, saying "During the late '50s and '60s when I was more engaged, [Sanders] was not there. I did not see him around. I have never seen him in the South. But if he was there, if he was involved someplace, I was not aware of it."

In a January 2016 interview, Lewis compared Donald Trump, then the Republican front-runner, to former Governor George Wallace: "I've been around a while and Trump reminds me so much of a lot of the things that George Wallace said and did. I think demagogues are pretty dangerous, really... We shouldn't divide people, we shouldn't separate people."

On January 13, 2017, during an interview with NBC's Chuck Todd for Meet the Press, Lewis stated: "I don't see the president-elect as a legitimate president. He added, "I think the Russians participated in having this man get elected, and they helped destroy the candidacy of Hillary Clinton. I don't plan to attend the Inauguration. I think there was a conspiracy on the part of the Russians, and others, that helped him get elected. That's not right. That's not fair. That's not the open, democratic process." Trump replied on Twitter the following day, suggesting that Lewis should "spend more time on fixing and helping his district, which is in horrible shape and falling apart (not to [...] mention crime infested) rather than falsely complaining about the election results," and accusing Lewis of being "All talk, talk, talk – no action or results. Sad!" Trump's statement about Lewis's district was rated as "Mostly False" by PolitiFact, and he was criticized for attacking a civil rights leader such as John Lewis, especially one who was brutally beaten for the cause, and especially on Martin Luther King weekend. Senator John McCain acknowledged Lewis as "an American hero" but criticized him, saying: "this is not the first time that Congressman Lewis has taken a very extreme stand and condemned without any shred of evidence for doing so an incoming president of the United States. This is a stain on Congressman Lewis's reputation – no one else's." The New York Post noted that Lewis used the "same unfounded, cookie-cutter personal attacks against Republican after Republican".

A few days later, Lewis said that he would not attend Trump's inauguration because he did not believe that Trump was the true elected president. "It will be the first (inauguration) that I miss since I've been in Congress. You cannot be at home with something that you feel that is wrong, is not right," he said. Lewis had failed to attend George W. Bush's inauguration in 2001 because he believed that he too was not a legitimately elected president. Lewis's statement was rated as "Pants on Fire" by PolitiFact.

There is more to this great mans life but here were just the steps he took to make Good Trouble.